Architect Kathleen Lechleiter ’81, ’82 is shaping safe, stable, and dignified housing in Baltimore neighborhoods.

Read MoreComponent Parts: The Making of an Engineer’s Legacy

His middle school principal said he wasn’t cut out for high school. The U.S. Marine Corps said he was too small to enlist. But no matter how often people told him no, Joseph Stanislao found a way to achieve the impossible and make greater access to education his legacy.

Story by Micaela Gerhardt | Photos by Seth Anderson, the NDSU Archives, and Kensie Wallner | April 16, 2024

At the age of 95, Joseph (Joe) Stanislao, P.E., stands at 5 foot 2 inches — small in stature, but big in ambition. He grew up in Manchester, Connecticut, a first-generation American born of Italian immigrants. Among his earliest memories are visits to the local fire department, where he would sit and play pretend in the driver’s seat of a fire engine, the enormity of the steering wheel forever cementing itself in his memory.

He had a pleasant childhood. He laughs as he recalls critiquing the little homes his classmates built out of blocks, sensing at a very early age what his engineering education would later affirm, that the toy structures were not designed properly. But in the seventh grade, tragedy struck, and Joe lost both of his parents.

“I had to care for myself. I had to figure out a way where I was going to live,” Joe said. “I was somewhat of an orphan, but I wouldn’t tell anyone for fear that they would put me in some kind of home or lock me up … I was totally on my own.”

He continued going to school. A year after the death of his parents, when Joe was in the eighth grade, the assistant principal told Joe he wasn’t cut out for high school because his speech and grammar were inadequate; he recommended Joe attend trade school instead.

“I said, ‘Before I make that decision, I need to go home and talk to my parents.’ I didn’t tell them I didn’t have any parents,” Joe said. “A couple of weeks later, I came back and said, ‘We had a very intensive discussion. [My parents] recommended, and I agreed, that I should go both to high school and trade school.’”

“Well, Joseph,” the school administrators said, “it’s not possible. You can’t do that.”

But it was, and he could. In 1948, Joe graduated with a high school diploma and a certificate in trade. Shortly after, he began his career as a tool and die maker and a draftsman, making detailed technical sketches for Pratt & Whitney, a manufacturer of aircraft engines.

“Si puo’ togliere tutto ma non l’istruzione,” Joe’s mother had often reminded him, in her native Italian and in English, “They can take everything away from you, but they can’t take your education.”

Joe’s commitment to education led him to serve as the dean of NDSU’s College of Engineering (then known as the College of Engineering and Architecture) for 18 years, from 1975 to 1993. He has since established himself as a major benefactor of the College, with a legacy plan to provide scholarships for students in all six engineering disciplines at NDSU.

When Joe first arrived on campus, then-president L.D. Loftsgard asked, “Now that you’re here, what are you going to do for us?”

Joe replied, “I plan to fill the classrooms with outstanding students and bring industry to NDSU’s campus.” With the goal of increasing enrollment, Joe began traveling across North Dakota and Minnesota to talk to high school students about the opportunities at NDSU. Often, he partnered with NDSU Extension to visit rural communities and give lectures on topics like tractor design right on the farm.

“It’s why I like North Dakota — the people were always very gracious,” Joe said. “For a guy who started off in seventh grade … I didn’t know where I was going to sleep that night or what I was going to eat … To have people treat me the way they did made me feel like a king.”

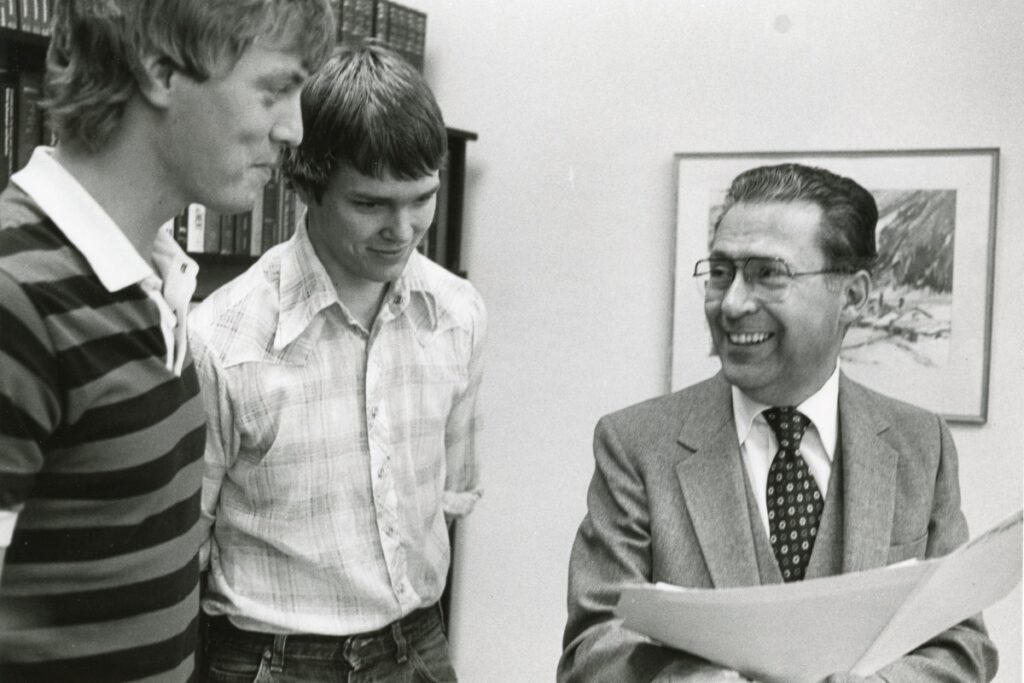

Joe Stanislao served as dean of NDSU’s College of Engineering from 1975 to 1993. Photos from the NDSU Archives

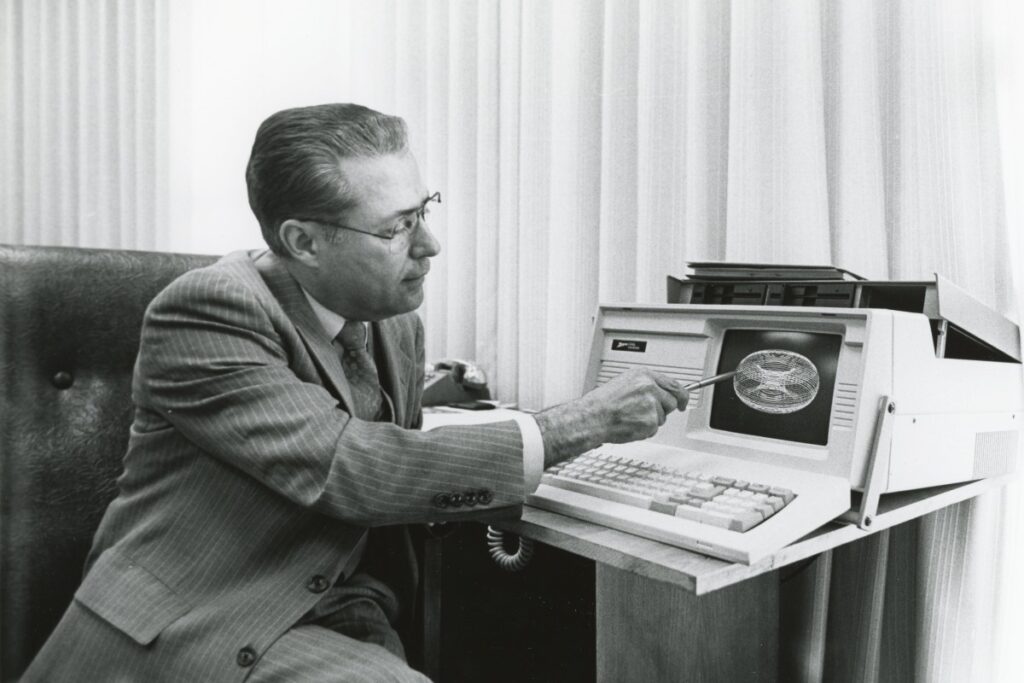

Joe believed deeply in bridging education and industry. In 1983, Joe and the economic development director for North Dakota, Sylvan Melroe ’57, steered the purchase of a $650,000 Control Data computer to help support manufacturing across the state.

At the time, many small manufacturing plants in North Dakota did not have access to a computer or a full-time engineer. By establishing the Robert Perkins Center for Computer Technology at NDSU and providing access to a computer and mechanical engineering students, Joe and Sylvan supported regional businesses in the design and manufacturing of equipment. One major manufacturing company in the state used NDSU’s computer for nearly 10 years.

“The thing I liked about Joe — he could take the theory, he understood that, and make it practical,” Sylvan said.

Joe’s efforts and genuine relationship-building resulted in more than twice the number of faculty, double the number of degree programs, and nearly four times as many students in the College.

One of those students was Jenny Hopkins ’83, an industrial engineering graduate who currently serves as an NDSU Foundation Trustee. When Jenny came to NDSU, she attended an informational meeting in the College of Engineering, where there were maybe five other female students in the room. There, she met Joe — short, but a force of nature, she remembers. When he told Jenny she should be an engineer, she trusted him and said, “OK, I’ll give it a try.”

Joe continued to support Jenny throughout her four years in the industrial engineering program. When Jenny struggled with calculus, Joe called her professor and arranged for her to sit outside his office every day and do her homework. He found money for Jenny and her fellow industrial engineering students to attend a regional conference. He nominated her to speak at commencement.

“He was just a really hands-on dean, always,” Jenny said. “He was very pro-women when it wasn’t that cool to be pro-women … I believe he had a fundamental belief that women should be in engineering or that women could do whatever anybody else could do.”

Being challenged and championed by Joe helped Jenny stay the course — even when engineering was “miserably hard.” Jenny’s experience at NDSU empowered her to pursue a master’s degree in industrial engineering at Stanford University and helped prepare her for a highly successful career, which began with the technology company Hewlett Packard and evolved into owning and growing businesses as an entrepreneur. She and her husband, Mark, support NDSU engineering students with an endowed scholarship and a pledged gift to the Richard Offerdahl ’65 Engineering Complex.

As Jenny thinks about where she started — washing blackboards in Minard Hall every night to help pay for tuition — to today, she can’t think of anyone at NDSU who deserves more thanks than “Dr. Stanislao.”

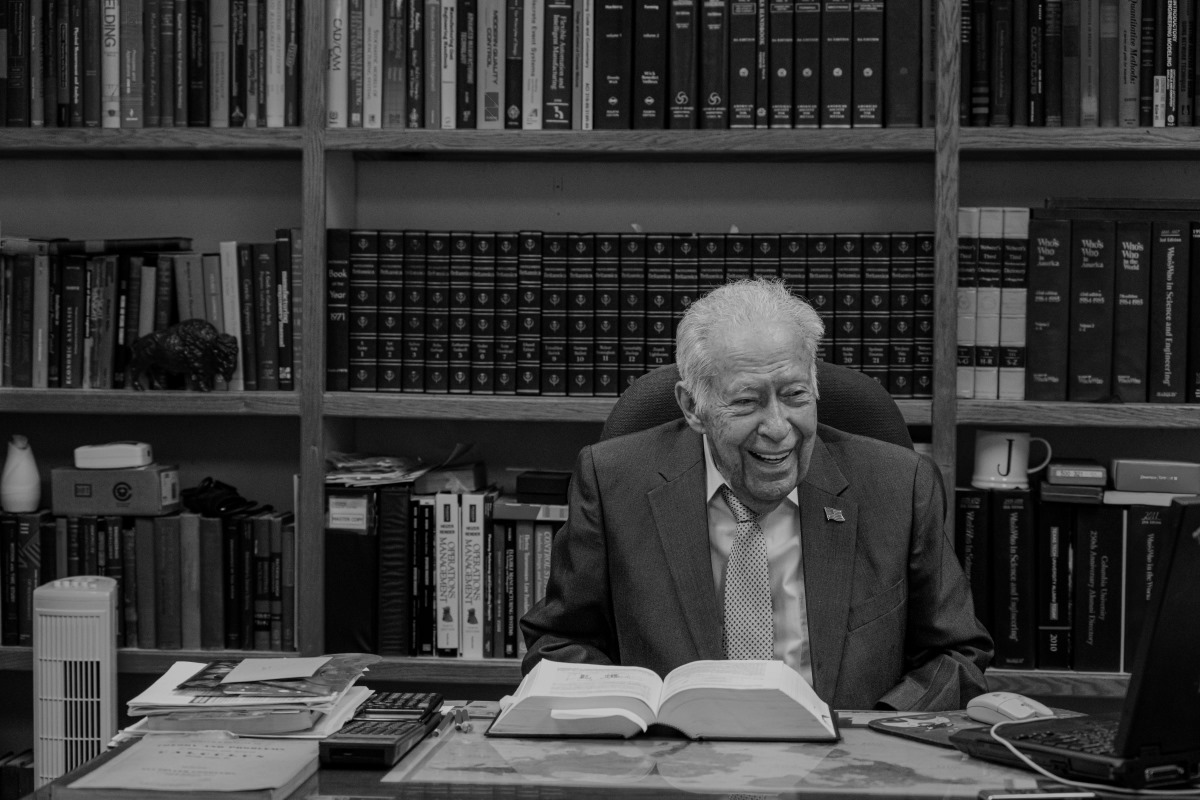

Joe maintains a career as an engineering consultant, taking on one client at a time. He says he isn’t the first person anybody calls these days, but when someone has an engineering challenge that can’t be overcome, they eventually find him — though he doesn’t have email, a cell phone, or a phone in his office.

His workspace is intentionally quiet and secluded, lined with every book he collected during his education, from freshman year to his postdoc. It’s a place he goes to think, draw, innovate, and find solutions for his clients.

“That’s the way I make my money to pay for the scholarships,” Joe said cheerfully.

In 2020, Joe’s wife, Bettie, passed away, and Joe began reflecting on their life together and how to best honor their passion for education. He was determined to invest in students, because he knows from experience that earning a college degree requires grit.

Both Joe and his late wife, Bettie, shared a passion for education and NDSU. Of all the universities where he worked, Joe says NDSU gave him the most fulfilling opportunities. Photos by Seth Anderson

After leaving his first job at Pratt & Whitney, Joe enrolled at the University of Connecticut, but didn’t meet the math requirements, even with a high school diploma. Discouraged, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps, which promised to pay for his college degree after three years of military service — but the Marine Corps, too, turned him away, saying Joe was simply “too small.”

“‘Sir,’ I said, ‘a bullet does the same to small people as big people,’” Joe said. “Finally, they were convinced that maybe I was sincere, so I found myself in boot camp in South Carolina.”

When he was discharged after three years of service, Joe enrolled in a junior college, then transferred to Texas Tech University for his bachelor’s degree. After Texas Tech, he moved on to Penn State for his master’s. There, Joe was awarded his first scholarship, worked for the Navy designing torpedoes in the underwater laboratory, and met Bettie, a fellow graduate student with bright red hair who helped him rewrite his thesis. After Penn State, he attended Columbia University, where he earned his Ph.D. in industrial engineering. For years, he zigzagged all over the U.S. in his 1953 Buick Super in an ongoing pursuit of the one thing no one could ever take away: his education.

His cross-country travels continued after earning his degrees; Joe served as a faculty member or administrator at five different universities over a 57-year period.

“Of all the schools I’ve been associated with, NDSU was the one that gave me the most exciting opportunities to express myself professionally as well as personally,” Joe said of what inspired him to make NDSU a philanthropic priority. “I want to thank everyone at NDSU and the people of North Dakota for making my tenure so rewarding.”

Meredith Jenkins ’25, an industrial engineering and management major with a minor in Spanish, is a recipient of the Dean Joseph Stanislao Scholarship. As a full-time student, member of the Gold Star Marching Band, and an intern at Marvin, the windows and doors manufacturer, Meredith appreciates how scholarships help her afford tuition while she works to cover living expenses.

Meredith had the opportunity to meet Joe at a Homecoming Week scholarship luncheon in 2023. He told her stories about courses he and Bettie taught; being in the Marine Corps; and the consulting work he continues to do.

“Meeting someone who’s just so passionate about not only engineering, but life in general … it’s contagious,” Meredith said. “I think [one thing] that’s really great about Joe is that he started as an ordinary guy … Everybody in college, we’re all getting a degree, right? But it’s really impressive how much he did with it, and that you can do that [too].”

Share This Story

Related Stories

Structures of Connection

Joanna Slominski ’04 wants us to think differently about construction — it’s more than bricks and concrete.

Read More