Architect Kathleen Lechleiter ’81, ’82 is shaping safe, stable, and dignified housing in Baltimore neighborhoods.

Read MoreFrom NDSU to the Moon

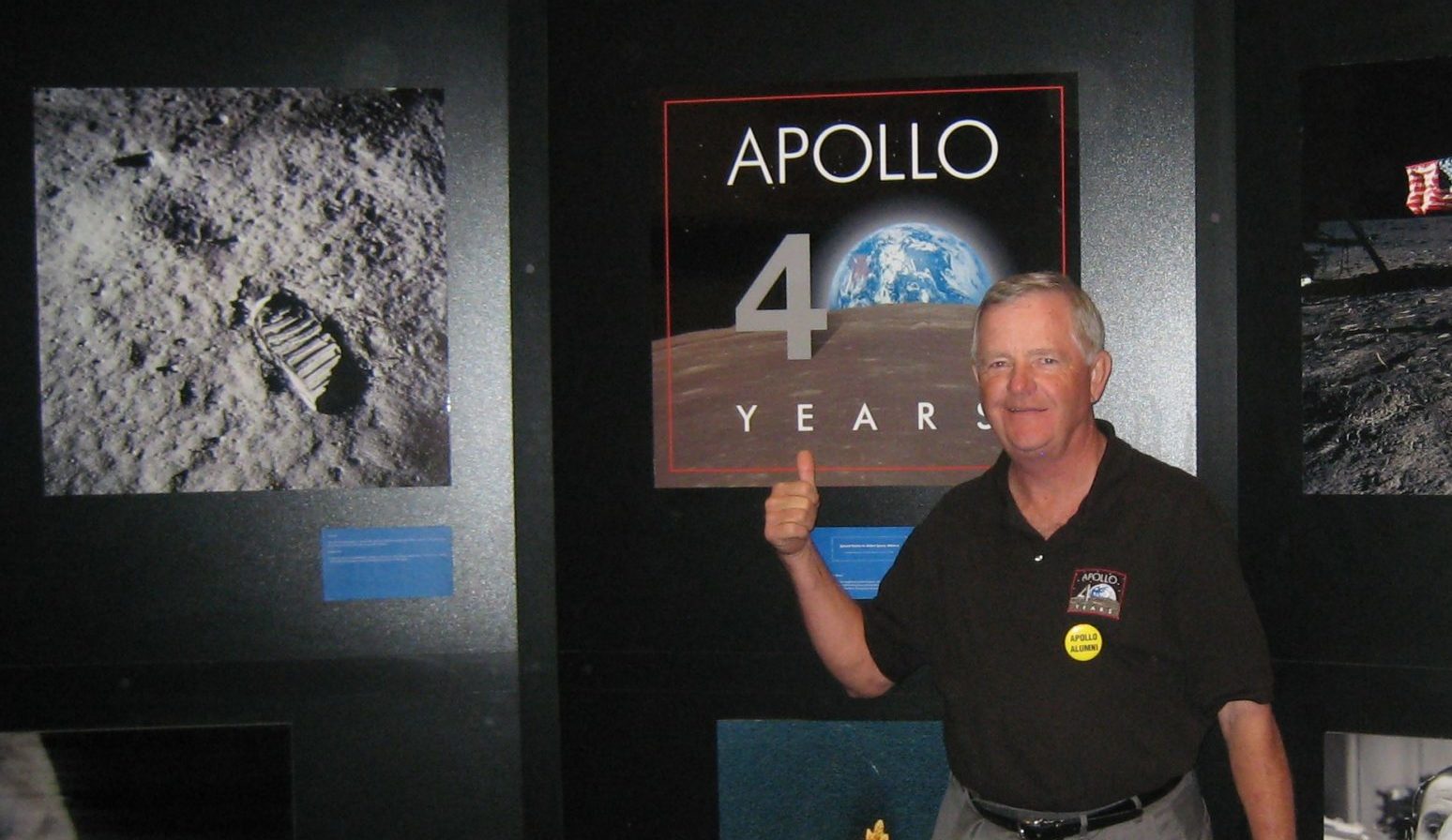

Jerry Siemers '61 describes how his NDSU education led him to a successful career with Boeing, including work with the acclaimed Apollo program.

By Micaela Gerhardt | March 11, 2021

In October 1957, Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, began orbiting Earth. As it raced overhead, Americans listened to radio broadcasts of its steady beeps — shrill and hollow. Mechanical —the sound a hospital monitor makes when it must alert the doctor that something is wrong.

Sputnik traveled quickly. According to NASA, it took only 98 minutes for it to complete its orbit around Earth. If the Soviet Union had the ability to launch Sputnik into the depths of outer space at such a rapid pace, Americans wondered, what else could they hurl beyond Earth, or across it? And what, or who, might be their next target?

Jerry Siemers of Bowbells, North Dakota, graduated with a mechanical engineering degree from North Dakota State University in 1961 — evidence that ordinary life continued even amid radical global and political change.

“I was just mechanically-minded,” Jerry said. “My dad and my uncles were repairmen and enjoyed building odd things, and then I kind of liked math and that side of the world, so it seemed like the right thing to do.”

That same year, the United States achieved its first successful test flight of the Minuteman missile, a long-range ballistic missile designed to carry nuclear warheads, built in response to Sputnik’s launch. After graduation and two years as a design engineer in the Airplane Co., Jerry drove his beloved ’51 Ford to the Air Force Base in Minot, North Dakota, where he continued his career with Boeing working on the Minuteman missile program. The Minuteman missiles, buried 80 feet below ground, were deemed a success — but in the 1960s, Americans also had their eyes on the sky. NASA began developing the Apollo program to advance the United States’ space technology and conduct scientific explorations on the moon — 238,900 miles away.

While working in Minot and at missile sites near Kenmare, North Dakota, Boeing offered Jerry a design engineer position with the Apollo program.

“NDSU had a good reputation so the Boeing company came and recruited us,” Jerry said. “Boeing was big on bringing in midwestern-educated engineers and other students because of the work ethics they got out of these employees. The turnover rate was not very high, so it was a good investment for the Boeing company to bring in guys like us.”

Jerry decided to make the move and travel beyond his comfort zone.

“I was young and single and never thought about going south but I said, ‘Hey, what the heck. I’ll go give it a try and check out the southern part of the United States,” Jerry said. “So here I go in my ’51 Ford to Huntsville, Alabama, and I’m part of the Apollo program.”

On Christmas Eve in 1968, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders watched from their spacecraft, Apollo 8, as Earth rose like a small, blue sun over the surface of the moon.

“There’s the earth comin’ up,” Bill exclaimed over a fuzzy broadcast signal. “Wow, is that pretty.”

As Jim scrambled to find a roll of color film, Earth slipped out of sight.

“Well, I think we missed it,” Bill said with audible regret.

But as the spacecraft rolled through the dark, Earth appeared again. Bill adjusted his camera settings, and in one swift snap captured a now famous photo, “Earthrise.”

Earthrise (Photo courtesy of NASA.gov)

Jerry, who worked in Systems Engineering and helped design ground support equipment for the launch vehicles, reverently remembers the moment he saw the photograph for the first time.

“The earth in the distance shows up as a jewel,” Jerry said. “I mean it’s very colorful. No one had ever seen it from that distance before, a couple hundred-thousand miles. But it was awesome, especially when you’re working down in the details — the mechanisms, the procedures, the training required, and all the things that could go wrong. It just seemed like an endless possibility.”

Apollo 8 became the first spacecraft to complete a circumlunar flight, making ten orbits around the moon before returning safely to Earth.

Through remarkable space explorations like Apollo 8, the United States triumphantly quelled collective fear of the Soviet Union by inspiring collective awe — if only for a moment. But the dust stirred in the 1960s never fully settled — Minuteman missile sites are still active in North Dakota today.

Jerry (center) receiving the Outstanding Leadership Award in support of NASA’s Space Operations in 2005. On his left is the Program Manager of NASA’S International Space Station program. On his right is the Director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center. (Photo courtesy of Jerry Siemers)

Jerry worked on all the moon missions during his time with the Apollo program and later contributed to the first international space mission, Apollo-Soyuz, a joint mission led by the United States and the Soviet Union. Jerry continued to work with Boeing through Boeing Petroleum Services, managing the Department of Energy’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve program. He later worked in international integration and program management with the International Space Station — his final title was Chief Engineer.

“It’s very pleasurable for me to think of my 42-year career with Boeing and how lucky I was to be involved in major national programs that all turned out to be successful,” Jerry said. “Things just fell into place and it all started at NDSU.”

Jerry is currently retired and lives on a lake in Sugar Land, Texas, where he has what he describes as a “wee little boat” that he likes to take on sunset cruises. He also golfs at the country club often, makes annual trips back to Bowbells, and enjoys traveling across the United States and to Australia, where his daughter’s family live.

Share This Story

Related Stories

Structures of Connection

Joanna Slominski ’04 wants us to think differently about construction — it’s more than bricks and concrete.

Read More